Building People Power Through a Community Benefits Agreement

Nashville, TN

Population: 500,000 - 1,000,000 | Government type: City & County | Topic: Community Benefits

OVERVIEW

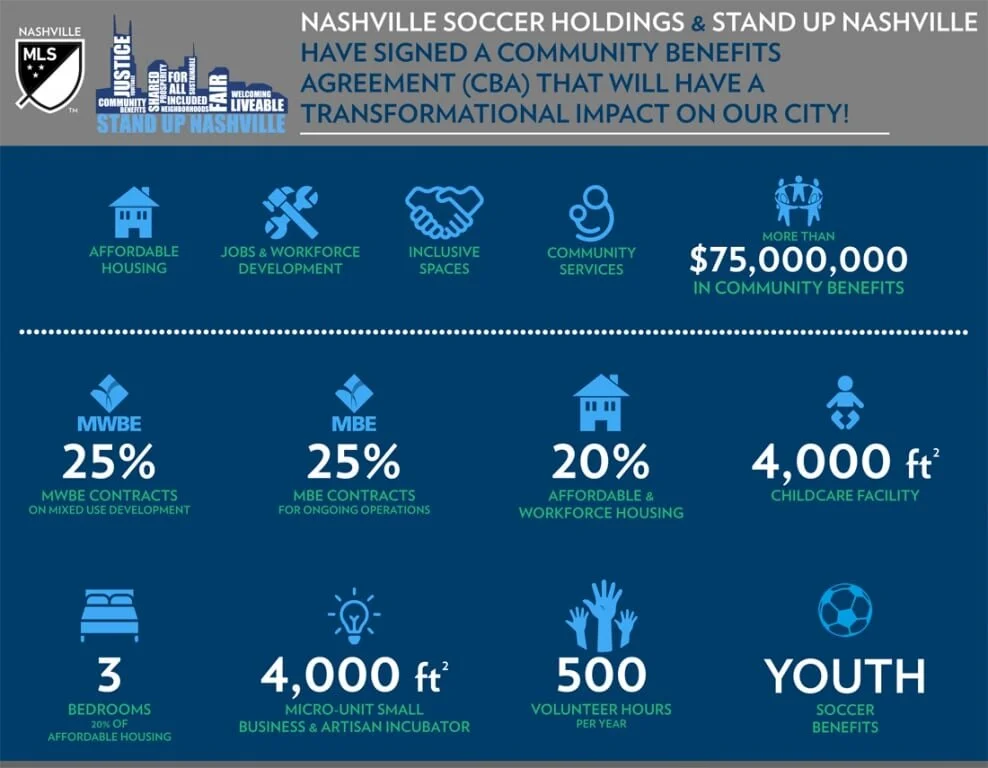

In 2018, Nashville became the first city in Tennessee to successfully negotiate a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) to provide affordable housing, $15.50/hour minimum wage, affordable childcare, and workforce development on a new private project. “Stand Up Nashville” (SUN), a community coalition group, signed the private community benefits agreement with Nashville Soccer Holdings, LLC (NSH). The agreement was on a 10-acre mixed-use development, in conjunction with building a stadium for the city’s new Major League Soccer (MLS) team. The goal was to shift the power dynamics of development in Nashville to ensure a meaningful investment in local communities and to create high-quality jobs rather than an extractive project that only benefits private entities.

In 2017, MLS named Nashville as a potential site for its newest expansion team, prompting the city council to approve a plan to issue $225 million in revenue bonds for a new stadium project if selected. Council members expressed concerns as to whether minority and women-owned businesses would be receiving contracts for the project. Community members also expressed frustration with the city’s priorities. The enormous subsidy was met with public resistance given that Metro employees had not received Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) and public schools and hospitals continued to be underfunded. It felt particularly egregious that the subsidy would go to a billionaire who would be further profiting from the city’s investment.

Nashville’s growth exacerbated racial and economic inequities that negatively impacted the city’s working-class communities. In response to the rapid gentrification of the urban core and a lack of pathways out of poverty, the mayor released an affordable housing report showing that the city needed 31,000 affordable housing units by 2025. As the city continued to prioritize businesses over its residents, public employees were also struggling to make ends meet and could no longer keep up with the cost of living in a rapidly changing city. This resulted in public employees, many of whom were forced to move out of the city, having to work multiple jobs.

The exponential growth of the city also coincided with two of the deadliest years for construction workers in Nashville, with 16 deaths in 2016 and 2017. The “Build A Better South'' report examined the working conditions of 1,435 construction workers in six major cities in the South, finding a direct correlation between the development boom and increasingly dangerous working conditions as well as rampant theft for construction workers. Nashville lawmakers faced preemption as they sought to address these problems by raising the living wage, passing local hiring provisions, implementing short-term rental regulations, and passing inclusionary zoning laws, in addition to amending its prevailing wage laws in response to new state regulations.

As a result, advocates collaborated with a small group of city council members to come up with a shared strategy to avoid state intervention if the city pursued a city-MLS CBA. Advocates focused on working toward signing a separate, private agreement with NSH regarding the surrounding mixed-use development, which would require council approval to rezone from Industrial Warehousing/Distribution to Specific Plan District. Per their collaboration, the council held off on a rezoning vote until the CBA was satisfactory. More than 30 of the 40 council members made public statements in support of the CBA, which was critical to the team’s overall business plan and its negotiations with MLS.

The CBA negotiated with NSH included:

20 percent of all housing units built at the development site will be set aside as Affordable and Workforce Housing with 3 bedroom units

NSH commitment to hiring stadium workers (ushers, ticket takers, box office janitorial, custodial, maintenance, field maintenance employees) directly from the community and paying them at least $15.50 per hour

4,000 sq ft for a childcare facility, which will operate on a sliding scale

4,000 sq ft to establish micro-unit retail spaces for artisans and local small businesses at a reduced rental rate

Mandatory safety training for all construction workers and supervisors

Leveling the playing field for responsible contractors that provide safe, gainful careers for their employees

Construction careers for individuals with barriers to employment, especially from Promise Zones, which are high poverty communities where the federal government partners with local leaders on a range of activities and priorities.

Inclusion of minority contractors

Collaborative Governance

The CBA was a result of a broad coalition of groups fighting together for a better deal. SUN, Nashville Organized for Action and Hope (NOAH), community groups, labor unions, churches, neighborhood leaders, families, and elected officials worked together to create a CBA that shifted power back to communities.

Each of the partners made a unique contribution to the coalition. SUN researched upcoming construction projects, strong examples of CBAs from across the country, and state preemption. They also hosted conversations with neighborhood associations, city council members, churches, and the mayor’s staff. SUN began hosting meetings to introduce the concept of CBAs to the community in early 2017 and worked to gather community input on what working people needed in order to thrive. SUN created and collected surveys to identify the top three desired benefits and suggestions for representatives during the negotiation process.

Local elected officials worked with the community to ensure the CBA negotiations continued to move forward. Councilmember Colby Sledge was instrumental in this process by setting up the initial meeting with developers. More than 20 city council members signed on to a letter to NSH expressing their desire for a robust CBA that was aligned with community needs before they were willing to hold a council vote on the MLS development. Council members also appeared and spoke at press conferences in support of SUN and the CBA.

While SUN and NSH were in deep negotiations for months, some city council members lent their voice to the process behind the scenes, helping both sides move toward agreement. During this time, SUN continued to put public pressure on the city council by mobilizing the community and encouraging residents to show up to public hearings on the legislation. It was critical to ensure that they had the necessary votes for both the rezoning change and the demolition approval in order to ensure the project moved forward.

SUN and NSH reached an agreement and released a joint statement in September 2018, just hours before the city council held a public hearing on legislation to rezone 10 acres of fairgrounds land for a private development next to the stadium.

Emphasis on equity

When entering this process, SUN had two goals. The first was to restore hope to residents who for so long had been sidelined from decision-making in the city. Their needs had been ignored and their votes marginalized—this fight was about reminding residents that they have the power, that this is their city to design and thrive in. The second goal was to secure the CBA with NSH to ensure that a wealthy corporation wasn’t the only winner in this arrangement, and that residents and working people benefitted from development too.

The CBA centered Nashville residents as the decision-makers in governance. This campaign proved that elected officials can govern and win elections without the undue influence of developers and without ignoring the needs of Nashville’s most vulnerable residents

Finally, the CBA is an important step toward dismantling the racist structure of state preemption, which is more prevalent in the south and prevents localities from taking bold steps to invest in workers and community. By centering the shared interests and needs of the community alongside private interests, the council was able to support a successful outcome that will have a positive impact in Nashville for years to come.

Analysis

States, particularly more conservative ones, may prevent local officials’ attempts to intervene or regulate community benefits agreements with private entities. However, in this instance, the local elected official’s role was to champion the community organizers and commit to the zoning changes necessary as the actual CBA was between community organizations and a private entity.

The Nashville City-County Council has 40 representatives that range across the political spectrum, ultimately making it moderately progressive. Support for the community organizing efforts around the CBA garnered momentum over time resulting in a broad show of public support at the county-city council level by the final months of the negotiations.

The Nashville example is one of a strong CBA, particularly in a southern state, and is the result of countless hours of organizing, negotiating and relentless determination by core community groups. The CBA provides solutions to help meet a wide array of community needs from child care to affordable housing and a higher minimum wage for jobs associated with the project.

Other examples

New York: This Kingsbridge National Ice Center Community Benefits Agreement included a plan to create a foundation to establish free after-school ice sports and academic tutoring programs for disadvantaged youth. The redevelopment was unanimously approved by the Bronx Borough Board.

Milwaukee: The Milwaukee Bucks and Alliance for Good Jobs Benefits Agreement included a wage of $15 an hour by 2023, a labor peace agreement, allowing all employees the opportunity to unionize, and a hiring program provision that 50 percent of employees will reside in the Targeted Hiring Zone comprised of zip codes with high rates of unemployment or underemployment. This CBA differs from the Nashville CBA in that its focus is solely on job pay and creation and did not address affordable housing, workforce development, or establishing a childcare facility.

Last updated: January 19, 2021

If you’re interested in learning more, please contact info@localprogress.org